By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

I spent nearly a week on the road at the end of September 2024, first speaking a couple of times at the Bogleheads Conference and then speaking three times at the American College of Emergency Physicians Scientific Assembly. This was actually most of the work I did in September, given that I spent most of that time healing from my fall at Grand Teton.

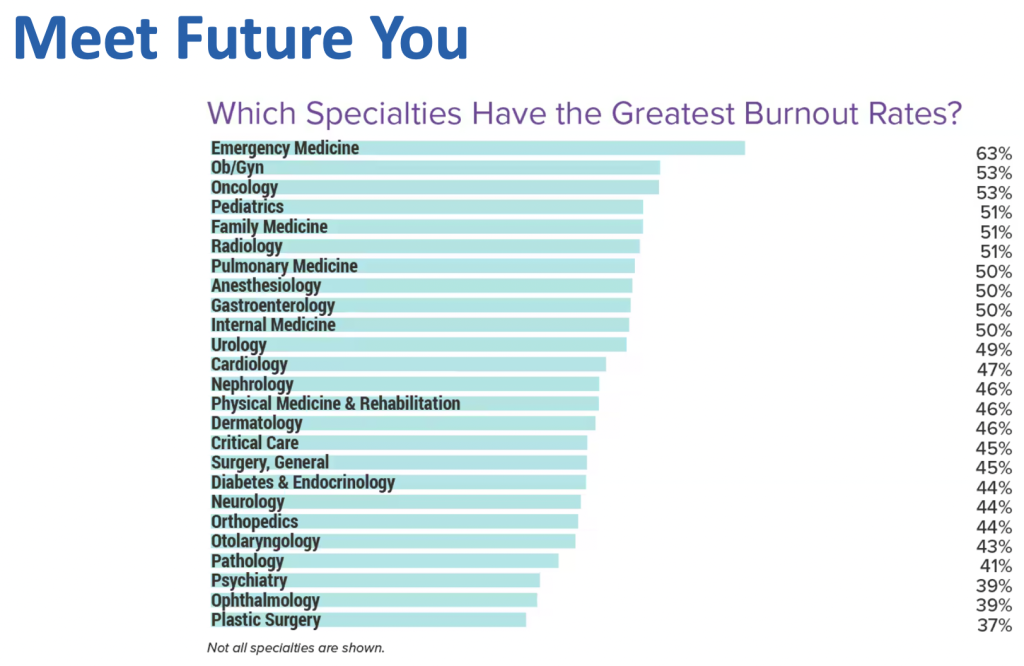

However, there were several things at the conference that caused me to think about burnout. One was a slide from one of my own presentations.

I made this slide using a chart from the latest Medscape Burnout and Depression Report. It shows that burnout in emergency medicine (EM) has not gone away 20+ years after I started. Back then, we attributed it to the fact that so many ED physicians were not residency-trained emergency physicians. I don’t think we can blame a 63% burnout rate on that anymore—if we ever could.

Change Specialties?

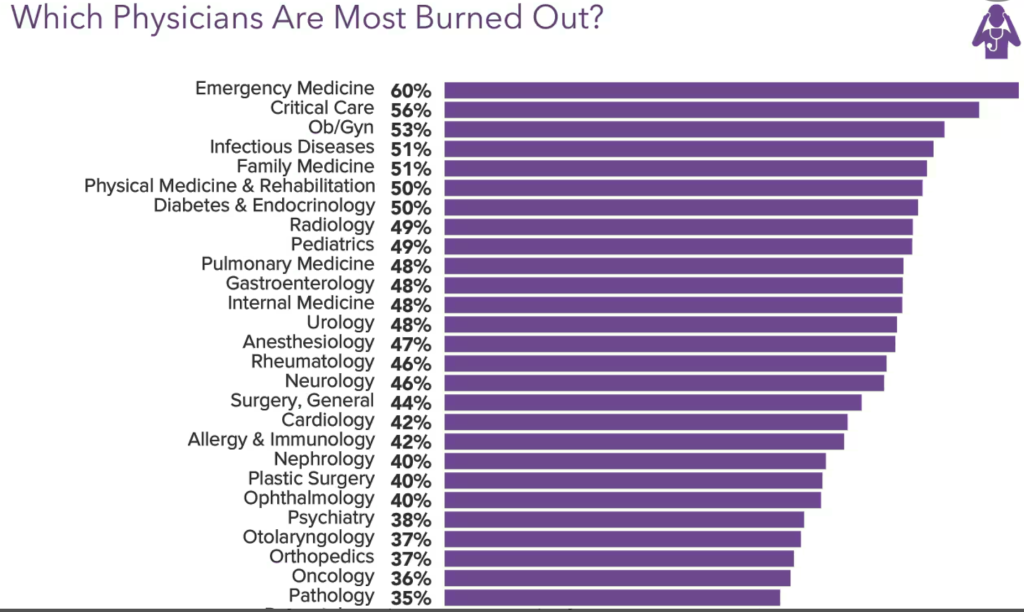

At dinner with one of my residency mates, she told me many of her residents are now doing critical care fellowships because they’re worried about burning out of EM. I found that somewhat bizarre, given that, in most surveys I’ve seen over the years, intensivists generally have burnout rates similar to and sometimes worse than those of emergency physicians. Here’s an example from the same survey from 2022:

Maybe the real story here is how critical care went from second to 16th in just two years. It might be pandemic-related, but they were 10th before the pandemic. Back to the subject at hand, though. I don’t think doing a fellowship that allows you to transition to another similar high-burnout specialty is the best way to deal with burnout during your career.

Schedule Vacations

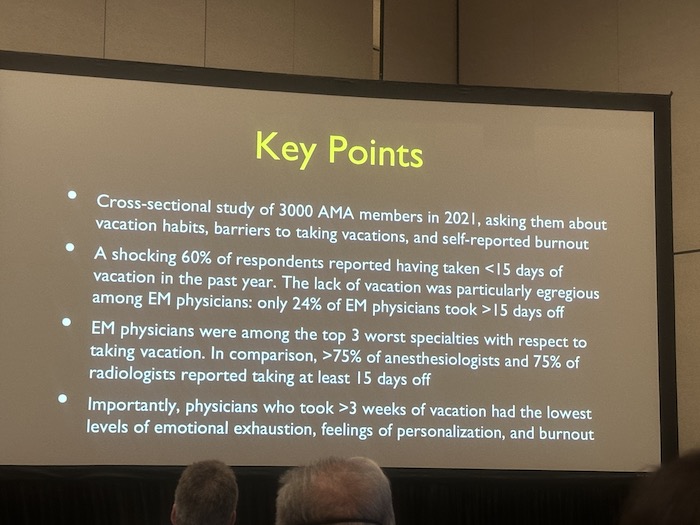

Let’s talk about some of the techniques that might work. Another interesting slide I saw at the conference was this one:

Notice that statistic. Only 24% of emergency physicians take >15 days off per year. How can that be, you might wonder? I think it’s because full-time emergency docs work 15ish shifts every month, no matter what else they do that month.

It’s December, and the kids are out for Christmas for two weeks? Still work 15 shifts. Same for summer trips and Thanksgiving and that CME conference in September. We just cram our shifts for the month together to create “days off.” Instead of working four shifts a week, we work 15 out of 16 days and then take a 10-day trip, often returning to another 15 shifts in 16 days afterward.

Fifteen shifts a month might not seem bad until you realize a few things:

- There are no “clinic closures” for federal holidays or anything else.

- Most emergency docs work rotating shifts and lose a couple of days a month to transition days. If you go to work at 10pm, which day did you have off? I assure you that it feels like neither, yet there is only one shift in two days. Same thing when you finish a string of nights and walk around like a useless, grumpy zombie for the next two days.

- Emergency docs work even on days there are no shifts. It might be doing charts, attending a meeting, or handling an administrative task of some kind.

Add a couple of administrative days, two transition days, and nine days of weekends a month, and you can quickly see that 15 shifts basically eat up the rest of the days in a 28-day month. In a 31-day month, that leaves three days for “vacation.”

The first thing that emergency docs can do to reduce burnout is to take some vacations where they actually work less, i.e. have months where they work less than 15 shifts. There are two ways I’ve seen this done.

The first is to just work fewer than 15 shifts all the time. This is my approach. As I cut back from 15 to 12 to eight and now to six shifts per month, I freed up 3-9 days a month to go on trips (and, in my case, work on WCI). If you also get rid of transition days by not working nights and eliminate administrative days by completing charts on shift and saying no to committee assignments, you might find a few more days, too. The nice thing about this method is that it allows you to go on a vacation every month. The problem, of course, is that you’re working less and earning less. Twelve shifts pay 20% less than 15 shifts.

The second way is a method used in some groups where, once or twice a year, each doc is scheduled for fewer shifts. Instead of 15 shifts, maybe you get 10. In some groups, you get paid less that month, and in some groups, you get paid the same (basically a bit of each month’s earnings is saved up to be paid out in the next “vacation month”).

More information here:

Which Medical Specialties Are the Most Burned Out?

Emergency Medicine’s Popularity Plummets

Stop the Nights

Let’s get real for a minute about the problem with emergency medicine. My neighbor the radiologist leaves for work at about 7 in the morning and is home at about 5, at least the days he works at the hospital. Given his subspecialty and contract, he doesn’t read ED films. My neighbor the pediatrician leaves for work at about 8 in the morning and is home at about 6—except for Wednesdays, which he takes off. He does have call responsibilities at times but rarely has to actually go into the hospital in the evenings and after midnight. An emergency doc, however, must be physically present in the ED every single night. Many groups divide these up evenly, so everybody gets their share. Other groups have dedicated “nocturnists,” who either prefer these shifts or simply get paid more to work them.

Let’s be honest. Nights suck. I mean, there are a few rare people who like them, but, mostly, working nights is painful. It doesn’t feel good to be awake at 3am. It disrupts the rest of your life. The pathology is far less interesting (lots more drugs, alcohol, and psychiatric comorbidities). It’s even a cardiac risk factor. That might not seem so bad at 35, but it’s a rare emergency doc who still likes working night shifts at 50. If you want to cure burnout, your group needs a night shift solution so that the majority of doctors in the group are not working night shifts at all.

In my experience, the best night shift solution is a massive night shift differential. In our democratic group, we sat down and figured out how much more a night shift would have to pay for people to work them voluntarily. It worked out to be about 50%, i.e. it pays 50% more to work a night shift than a day shift in my group. If you pay $2,000 for a day shift, you need to pay $3,000 for a night shift to get them voluntarily covered. Who volunteers to cover them? Two groups of people.

- People who want to make more money. These are generally young docs with student loans, a big fat mortgage, and no retirement nest egg.

- People who want to work less but make the same amount of money. Instead of 15 days, they work 10 nights, earn the same, and go on a five-day trip every month.

The first modification I made in my life when I realized I had the money to do so was to drop my night shifts. Yes, it cost me some money. Yes, it was worth it.

Control the Evenings

Emergency departments are most busy in the evenings, from perhaps 5pm-1am. That means that in a department with more than single coverage, a larger percentage of your shifts involve a component of the evening. At my main site, there are five eight-hour shifts a day, starting at 6am, 10am, 2pm, 6pm, and 10pm. Plus, there’s a 10-hour APC shift starting at 1pm. Basically, four of the five docs and all the APCs working in a given day can’t really plan anything in the evening. This doesn’t seem like a big deal until your kid has a recital you want to see. Or you want to coach a soccer team. Or play on a soccer team. Or hang out with your friends with regular jobs. Or attend some other event with your partner. There are benefits to having your banker’s hours off. You can go shopping when no one else is out. You can go skiing when the lifts are empty. You can start The White Coat Investor. But after a while, you realize all those things that help with burnout (like, a real life) seem to happen way more often in the evenings.

There are three good solutions to this problem. The first is to start the day shift really early. If it starts sufficiently early (sometime between 4am and 6am should work), the day shifts will become unappealing. People will preferentially work in the evening, and you can have as many day shifts as you want. The second is to pay an evening shift differential. This works just like the night shift differential. Fewer people want day shifts so those feeling burned out can have as many of them as they want and have their evenings back. Finally, you can institute a really great shift trading culture. If you can swap out your evening shifts when something really good comes up in the evening, you can make it to many of those burnout-defeating evening activities.

My group has done all three of these. The shift trading culture alone allowed me to play on a hockey team, but it wasn’t enough to play on three teams and coach two others. I needed all my evenings off to do that. Interestingly, our evening differential went away recently because enough people just hated getting up at 5am to come in for a shift starting at 6am.

More information here:

How My Burnout Led to Rage That Could’ve Ended My Career

What We Can Learn About Work-Life Balance and Retirement from the French

Work Less

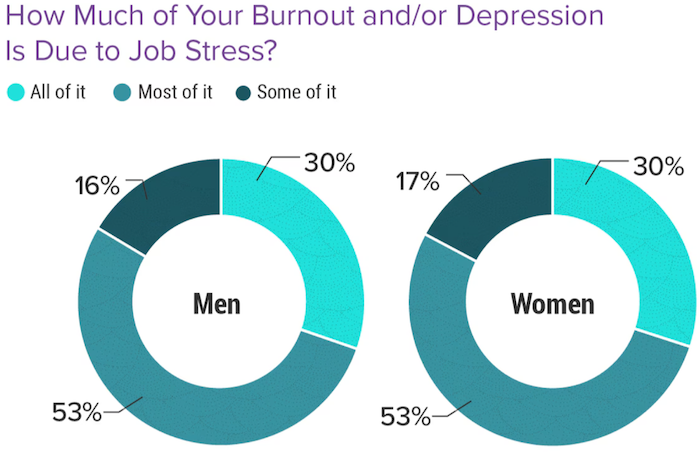

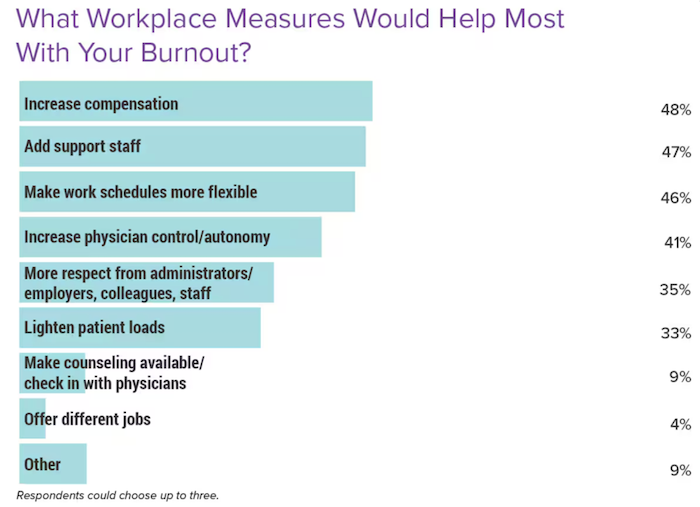

Another obvious burnout solution is to just work less. Maybe this isn’t as obvious as it should be. Check out this series of slides I used in a presentation recently that also comes from this year’s Medscape Burnout Survey:

OK, burnout is coming from work. What do we think would help reduce it?

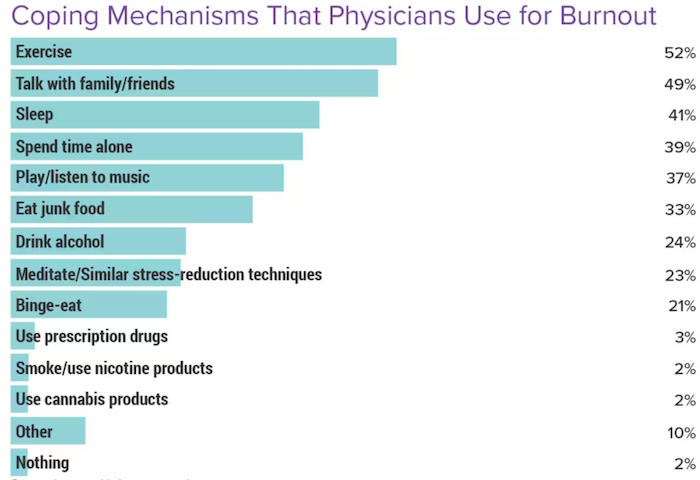

Wait? Not one person said to work less? Increasing compensation would allow one to work less and make the same amount of money. Increasing support staff would allow one to work less while at work. It’s the same with lightening patient loads. But it doesn’t appear cutting back was even an option in the question. They did ask what people did to treat their burnout, though:

Maybe we do something healthy like exercising, building relationships, or sleeping, but it appears that many of us just become loners, eat crap, and smoke crap. Apparently, nobody thought about cutting back.

The first thing I ask anyone who is burned out is, “Have you thought about cutting back to full-time?” And if you’re already just full-time, you might try cutting back a little more. My original financial plan drawn up as a resident called for me to be working six shifts a month by age 51. The needs of WCI forced me and financial success allowed me to get there a little earlier. I’ve combined this with dropping nights and evenings, too. But I challenge you to burn out when you’re working six day shifts a month. I don’t think it’s possible.

It’s probably not even that smart financially for me to continue to work. Medicolegally, I have more to lose than gain, and besides, more effort put into WCI would probably grow it faster and generate more than my clinical income anyway. Yet, as I sit here writing this six weeks into my 10-week short-term disability from falling off a mountain, guess what I miss a lot? Yeah, just being a regular old doctor.

Staff Adequately

Another painful thing about emergency medicine is when you’re always running around like a chicken with your head cut off. We all learned in residency to see four patients an hour and make sure none of them die. But guess what, it’s a lot more fun and a little more safe to see 1.5 patients an hour. That requires more doctors to be on shift, which means the doctors get paid less. But it’s probably worth it long term. The biggest financial risk you run is burnout.

Eliminate Pain Points

There are always some problems you can complain about. But if it’s the same problem over and over again, it’s time to do something about it. Form a committee, line up the troops, get administration involved, and pound on that biggest pain point until it’s gone. Then, start working on the next one until the remaining issues feel trivial. This will help you to feel in control instead of powerless, which is also good for burnout.

More information here:

Strengthening Your Mental Health

Understanding Veterinarian Burnout and Mental Health

Plan for Early Retirement

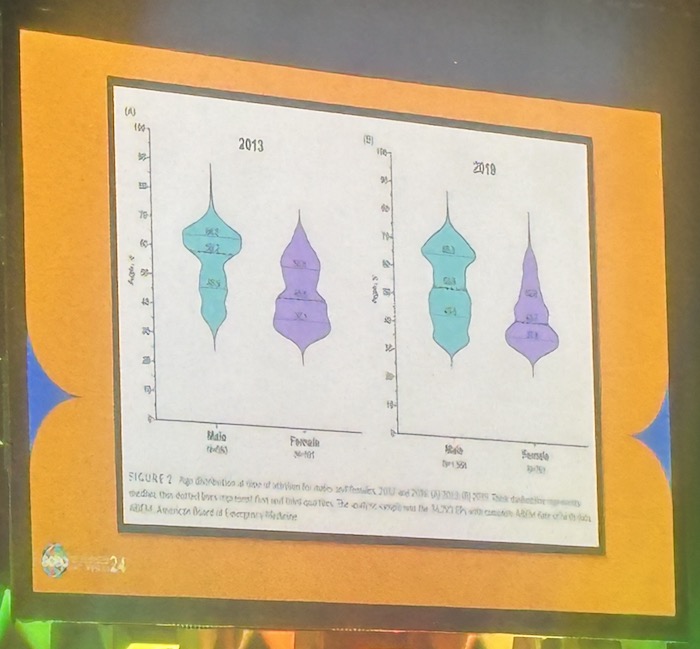

I wanted to share one more slide I saw at the conference.

I didn’t totally grasp this chart (and my picture is out of focus), but I think the Y axis is age and the width of the graphs is the number of docs leaving the specialty. The baby blue is men, and the purple is women. Apparently, women emergency physicians are now retiring (or at least leaving EM) at an average age of 43. It’s a little better for men, but the trend from 2013 to 2019 is terrible.

My point in sharing it is to demonstrate two things. The first is the importance of actually doing something (preferably multiple somethings) to stave off burnout.

The second is simply to show how important it is for emergency physicians to live their financial lives consistent with a FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) philosophy, because there is a surprisingly good (and increasing) chance you’re going to want to FIRE. If you want to retire after 13 years on an income of $150,000 in today’s dollars, you’re going to need to save just over 50% of a $400,000 gross income each year. Even if you’re OK working 15 years and living on $80,000 after that, you’re still going to need to put away $93,000 a year. Remember my 20% savings rate guideline is for a full career. That’s not going to cut it for FIRE.

Burnout is a real problem in the house of medicine, but it is particularly bad for emergency physicians. Live your financial life in such a way that you can implement burnout-reducing changes. The more you have and the less you live on, the more you can do when burnout rears its ugly head.

What do you think? What can doctors do to reduce burnout? Why is it so bad for emergency docs right now?